Series of photographs taken under the M25, made in collaboration with Nick Rochowski including sound by Matthew de Kersaint Giraudeau.

Waiting for the wave

(In January 2012 I spend a night with Tim and Nick whilst they take some of these photos. In the summer, I go out with them again to record some sound for an installed version of the Hind Land project to be exhibited in Portugal.)

Tim, Nick and I are walking down a dark, overgrown path towards an underpass beneath the M25. Nick has a torch and he points it ahead of us, lighting the way. He stops for second and says “I think I just saw someone”. We all flinch with fear, but it’s probably just kids messing about on the private land under the road.

The motorway bridge is huge, passing over a river and a train line that we can hear but not see. We drink cans of beer and talk in whispers whilst I record the different sounds of the road. We forget about the person Nick saw on the way down here. We don’t see any other movement until we finish the recordings, walk back up the path to our parked car, when suddenly two huge Alsatian dogs run out of a house and bark at us until we drive away.

All around the M25 are underpasses: some of them are small openings that allow streams to run underneath the motorway; others are bridges, crossing small roads or footpaths; and some are concrete tunnels just wide enough for farmers to drive tractors between their fields, divided by the building of the road.

Tim Bowditch and Nick Rochowski are, slowly but surely, visiting every one of these crossings – circling the motorway and photographing the incidental subterranean environments created by the M25.

I spent a winter’s night with them down there, underneath the M25. When they said that they were taking long exposures, I thought they meant a minute, or maybe two. Actually, the exposures can take up to an hour, and that time is then doubled by the in-camera processing. That adds up to a long time crouching in the cold dirt beneath a motorway.

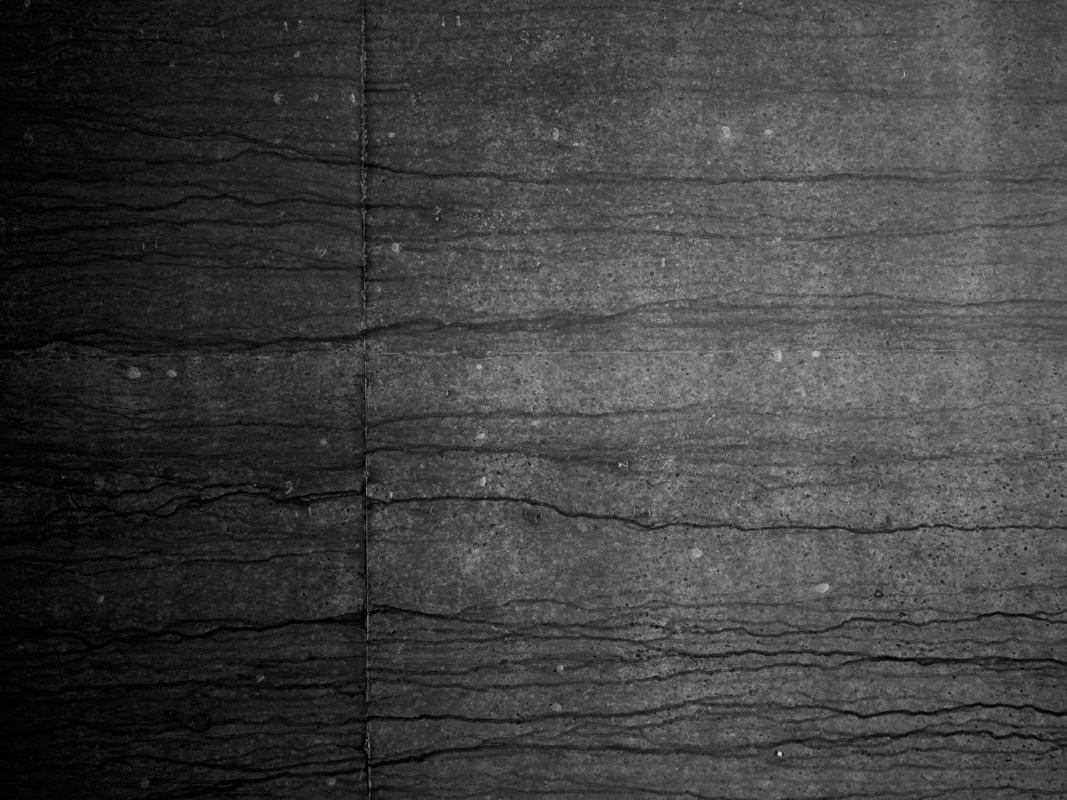

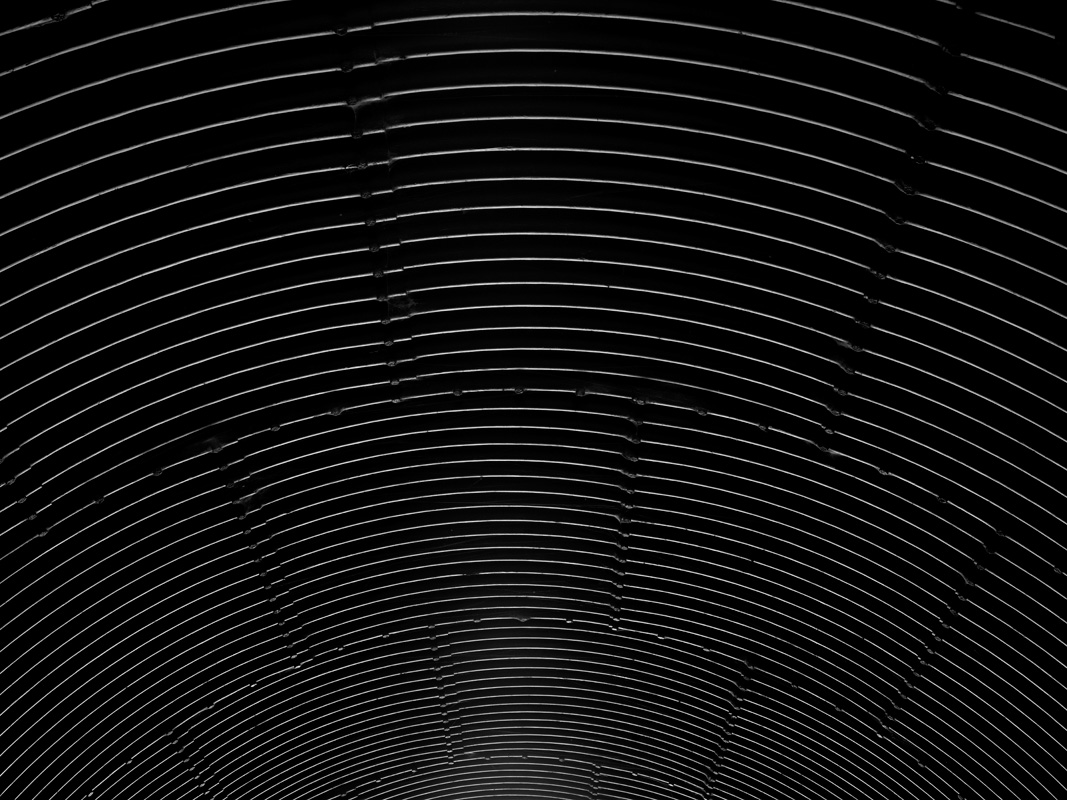

They take the photos at night, that’s why they need the long exposure times. The camera Tim and Nick are using for the project has an achromatic digital back. This means that it can take photos in almost total darkness because it picks up the entire light spectrum, including infrared waves. The camera takes in a huge amount of visual information. Concrete structures are rendered in breathtaking textural detail – looking closely at the prints is like taking a magnifying glass to the surface of another planet.

These places are the sort of dead zones that feel haunted by unseen human activity. The M25 is right above you. You can hear the suspension of the road working constantly – echoing, clunking, swishing noises. The traffic is lighter at night, and standing under the bigger bridges you can pick out the approach of an individual vehicle, hear the ‘be-doink’ sound as it passes over the suspension directly above your head, and then a strange whistling sound as it speeds away. And this sound, back and forth above your head, is endless. The traffic doesn’t stop and it doesn’t know, or care, that you are listening.

From far away the road sounds like the sea, almost soothing. Up close it is more like a factory. The noise never ceases and it is inseparable from the functioning of the motorway. If the road sounds like a factory, maybe the noise is the product of its strange, endless industry. Or maybe the noise is a symptom of some deep urban pathology – the tinnitus ridden ear canal of a giant.

The photographs, unlike the motorway itself, are deathly quiet. No cars, no humans, no graffiti on the walls. The only plant life is dead, fallen under the rivers that run beneath the road. Tim and Nick are visiting a deserted world, and their photographs are quiet, detailed observations of their time spent there.

The photographs allow you to examine the architectural details of the motorway. The poured concrete structures were created with ‘shutters’, moulds made from timber, and the concrete retains the mark of the wood grain on its surface. These shutter marks were a deliberate gesture in much Brutalist architecture – an aesthetic recognition of the building process. But who is ever going to spend long enough looking at these motorway bridges to form an aesthetic judgement? Most people only ever see the underpasses from a car, which doesn’t allow much time to ponder the methods and materials used in their construction.

With their intersecting planes of concrete and steel, the photographs make the underpasses look like greyscale temples – shrines to the motorway above. But the aesthetic of the underpasses was the product of base level pragmatism. Architects did make choices about how the structures would look, but form followed function in the most direct way possible. This is architecture to be ignored.

I was going to say that some of the images seem to be without scale – but that isn’t quite right. It’s more like some of the images are without human scale. Perspective is created within the photographs by the horizons of concrete and steel and water. The photographs work to their own scale.

Marc Augé wrote that motorways are non-places, transient zones that do not hold enough significance to be thought of as places. Then what are these underpasses, sitting as they do beneath the non-place of the motorway? They are the subterranean twin of the motorway non-place, inseparable from the road, but also invisible to it. Their only function is to allow cars, trains, water or pedestrians to pass through the space of the motorway.

To come back again to the sound of these underpasses, everything you hear is also ‘passing through’, because sound itself is transient – a wave: a momentary transmission of energy through matter.

These very static spaces are actually filled with momentary transmissions of energy: the sound, the vehicles overhead, the dripping water, the dog walkers who occasionally stroll through the pedestrian underpasses. And, for a few hours on some cold nights, Tim and Nick captured the other waves that fill the underpasses, the waves of infrared light that allowed these photographs to be taken.

But even photographers come and go. A few hours crouching in the dirt is nothing compared the stillness of the concrete and steel of the motorway bridges. After everything else passes through, only the road remains, waiting for the next wave.